When President Joe Biden was vice president, the Obama administration in 2016 did not renew key mineral leases for Twin Metals, the proposed underground copper-nickel mine in the same watershed as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, and initiated a 20-year moratorium on mining in the watershed.

But the Trump administration made quick work of reversing those changes, moves that revived the Twin Metals proposed copper-nickel mine project and paved the way for it to submit its mine plan to state and federal regulators in December 2019 .

Now, with Biden in the White House, environmentalists are hopeful, and industry supporters are worried, that the administration could reinstate the Obama-era policies.

But Biden’s position is unclear. While two of Biden’s cabinet picks — U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland, D-New Mexico, to lead the Department of Interior, and Tom Vilsack to again lead the Department of Agriculture — have already opposed copper-nickel mining in the watershed, Biden has also signaled support for boosting domestic production of metals like copper and nickel for the electric vehicle and solar industries.

Where the nominees stand

Both Haaland and Vilsack have taken positions against mining in the Rainy River Watershed, which is shared with the BWCAW.

Vilsack has been more forceful. When he was agriculture secretary under Barack Obama, the U.S. Forest Service, which is part of the Department of Agriculture, withheld consent on the renewal of Twin Metals’ mineral leases and initiated a study that could have banned mining activity for 20 years in the watershed.

“The Boundary Waters is a natural treasure, special to the 150,000 who canoe, fish and recreate there each year, and is the economic life blood to local businesses that depend on a pristine natural resource," Vilsack said in a 2016 news release announcing the decision . "I have asked Interior to take a timeout, conduct a careful environmental analysis and engage the public on whether future mining should be authorized on any federal land next door to the Boundary Waters."

Even after he left office, Vilsack continued to be a vocal critic of Twin Metals. In a 2018 opinion piece in MinnPost , he called restrictions on mining near BWCAW “one of the most important federal decisions affecting this special place since the signing of the 1978 Act,” and maintained that a mine’s boom-and-bust cycle would harm St. Louis, Lake and Cook counties’ high quality of life.

“A project like the proposed Antofagasta Twin Metals mine, which threatens the fundamental character and integrity of the Boundary Waters, puts all that at risk,” Vilsack wrote.

ADVERTISEMENT

In Congress, Haaland signed on as co-sponsor of H.R. 5598 , a bill authored by U.S. Rep. Betty McCollum, D-St. Paul, that aimed to permanently ban copper-nickel mining on federal Superior National Forest Land within the Rainy River Watershed.

And in April 2019, as chair of the subcommittee of National Parks, Forests, and Public Land, she said she was concerned the Trump administration's "Forest Service is similarly being pressured by an extractive agenda."

"In places like Minnesota, the Forest Service and (Bureau of Land Management) are jointly responsible for putting valuable fresh water resources at risk from mining pollution," Haaland said. "Our national parks, forests and public lands should be managed for all Americans not just a few."

Her backing of McCollum's bill drew the ire of U.S. Rep. Pete Stauber, R-Hermantown, a mining supporter who first privately urged colleagues to oppose Haaland’s nomination, and later publicly requested Biden withdraw Haaland’s nomination. The five tribal chairs in the 8th Congressional District were not consulted by Stauber ahead of his opposition and were appalled by his opposition. If approved, Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo, would be the first Indigenous cabinet secretary.

“As a colleague of Representative Haaland’s on the House Natural Resources Committee, I cannot turn a blind eye to the fact that she supported and voted for H.R. 5598, a dangerous piece of legislation that would eliminate quality jobs for many of my constituents on the Iron Range by placing a moratorium on mining before specific projects can go through a fair and science-based permitting process,” Stauber said in a news release Tuesday.

ADVERTISEMENT

Stauber has also shared concerns over Vilsack’s nomination in a MinnPost article and tweet from earlier this month. A spokesperson Wednesday would not say whether he penned letters to colleagues and Biden opposing Vilsack as he had with Haaland, but said “Congressman Stauber will continue to be vocal about his opposition in the weeks leading up to Vilsack’s confirmation hearing.”

Opponents of Twin Metals, like Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters and Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness, have backed the two nominees, issuing statements applauding their nominations.

In a statement to the News Tribune, McCollum said Vilsack and Haaland “have a record of understanding the importance of the Boundary Waters as a national treasure and taking action to protect it. As we confront global threats — especially climate change — the BWCAW’s pristine water will only become more of a precious commodity, as well as critical to the national security of the United States.”

What they could do

Together, the two agencies under Vilsack and Haaland could shape the future of copper-nickel mining in the Rainy River Watershed.

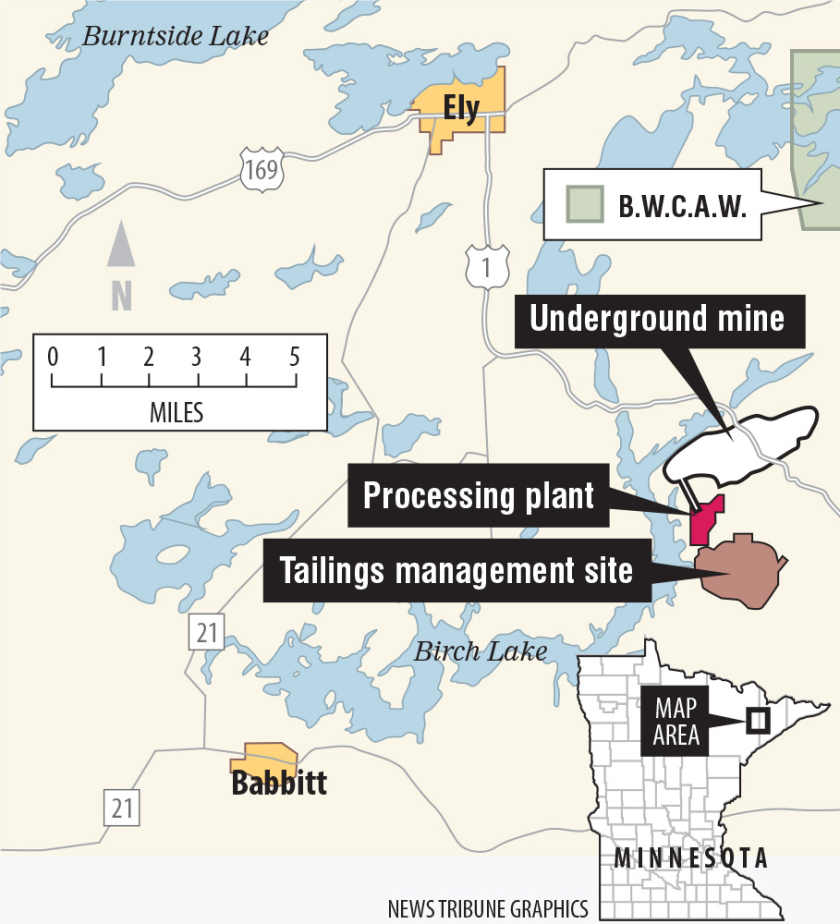

Much of the watershed, and Twin Metals’ proposed site, sits on federal land in the Superior National Forest.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Department of Interior’s Bureau of Land Management manages the mineral deposits underground and is currently in the early stages of reviewing Twin Metals’ mine plan while the Department of Agriculture’s U.S. Forest Service manages everything on the surface and must consent to the Bureau of Land Management’s decisions.

In 2016, under the Obama administration and then-Agriculture Secretary Vilsack, the Forest Service withheld consent to the renewal of two of Twin Metals' hard rock mineral leases, allowing the Bureau of Land Management to reject the lease renewal application.

At the same time, the two agencies moved to exclude 234,000 acres of the Superior National Forest south and west of the BWCAW from any future mining permits, most within the Rainy River Watershed but outside the BWCAW, calling it a “timeout” to see if copper mining would be appropriate in any part of the area. If officials determined it wasn’t appropriate, the mining could have been banned in the area for up to 20 years.

The Trump administration in 2018 reversed both decisions, renewing Twin Metals’ leases and ending the mineral withdrawal and accompanying environmental study.

Julie Padilla, Twin Metals’ chief regulatory officer, doesn’t want to see the Biden administration follow Obama’s lead.

“I think a rash decision to ban mining would be, frankly, irresponsible as we move forward,” Padilla said.

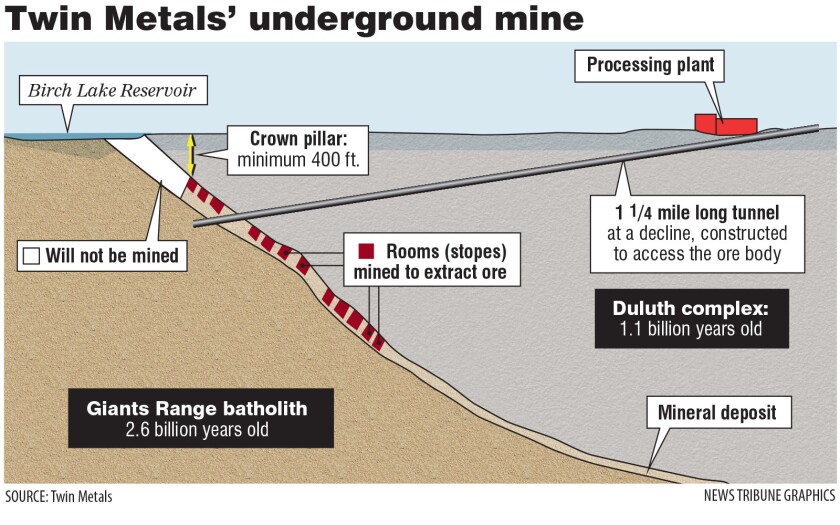

She noted that the company has since submitted its mine plan of operations to regulators and has made changes to its plan. Most notably, Twin Metals plans to store tailings, the waste rock left over after the valuable minerals are processed out, with the dry-stack methods on-site rather than mixed with water and stored behind a dam in the Lake Superior Watershed.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We’re in a much different place than we were back when we were working on renewing the leases, and, frankly, our project looks a lot different now than it did before,” Padilla said.

Twin Metals and other industry groups have long argued that moratoriums and widespread bans unfairly ban projects without regulators’ consideration of the specific project’s location, ore characteristics, type of mining and other factors.

Stauber on Monday introduced a bill that would prevent Biden, or any future president, from banning mining on federal land where it's already allowed — a preemptive attempt to prevent the reinstatement of Obama-era mining restrictions in the Rainy River Watershed. The bill, however, likely has little chance at becoming law due to the Democrat-controlled U.S. House, Senate and presidency.

Biden’s position unknown

Biden has yet to publicly discuss potential mining in the Rainy River Watershed or Twin Metals.

The Biden campaign last summer did not respond to repeated inquiries about it from the News Tribune and other media outlets.

ADVERTISEMENT

And in 2019, the Boundary Waters Action Fund, the political arm of Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters, went to Iowa to garner support for the BWCAW in the form of pledges from Democratic presidential candidates.

Neither Biden nor Vice President Kamala Harris, who was then also seeking the Democratic presidential nomination, made the pledge.

But just weeks ahead of the election, Reuters reported Biden’s campaign privately told mining companies it wanted to increase domestic production of copper, nickel and other metal for use in electric cars and solar panels.

That’s giving Padilla hope that the administration can be “educated” on the project and how it fits into Biden’s larger climate goals and shift to a greener economy.

“Incoming President Biden has talked about moving back to trusting science and trusting those fact-based processes,” Padilla said before Biden’s inauguration. “And that’s what the regulatory process is intended to do. It would be a highly political decision to halt the regulatory process where it sits right now.”

What about the state’s review?

Ahead of Twin Metals submitting its mine plan to state and federal regulators, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources announced it would conduct its own environmental review of Twin Metals, separate from federal agencies , in part because it had concerns over the Trump administration’s handling of the project.

Will it remain separate under the Biden administration? DNR Assistant Commissioner Jess Richards told the News Tribune it’s a question they’ve been receiving.

“There’s a lot that goes into that consideration,” Richards said. “It’s not just necessarily a timing issue, but there’s contractors at play and all kinds of different things that have already occurred, and so we’d have to weigh the totality of such a chance, along with the federal agencies before we would make a decision like that.”

Though the reviews are separate, state and federal officials continue to collaborate on the sharing of information and, in the meantime, that process will continue, Richards said.

“We don’t know whether the administration will make any changes to the environmental, federal environmental review process, but I would say it’s probably reasonable to expect it might take them some time to make those kind of decisions,” Richards said.